Nepal is well-known for flaunting a chain of the planet’s largest mountains, the Himalayas.

Mount Everest, which brags the tallest peak at 8850 metres, is the range’s poster child, featuring on wallpapers, films and every adventure junkie’s bucket list. The mountain is breathtaking – literally – as climbers need to pack bottled oxygen to survive its thin atmosphere if they dare to reach the summit.

At the feet of the iconic mountain, however, lays grass hills, plains and – the less-marketed – impoverished villages that are vulnerable to human trafficking and sexual exploitation.

In fact, Child Rescue recently rescued a Nepali woman who had been forced to dance in bars for five years after being trafficked into a nearby country.

Worse, she is a mere blip on the radar compared to a flood of women in the country being trafficked each year. In 2016, about 170,000 Nepali people were trafficked, according to Australian-based global anti-trafficking organisation Walk Free Foundation.

So why is the country a hot spot for trafficking and exploitation? To answer this question, we must deconstruct the country – piece by piece.

Harmony

Nepal, which is sandwiched between China and India, stretches about 500 miles from its east to west borders and has about 28 million people. One million of them live in the country’s capital, Kathmandu, known as the city of religious temples.

Most of the population live on the outskirts of cities.

According to the World Bank, 80% of the population live in rural areas. Many of them live in villages where houses are made of stone, bamboo or mud bricks and topped off with a thatched roof. The landscape is rugged too, with a third of the land covered in mountains.

While their surroundings might appear inhospitable, the people are known to be warm and welcoming, especially to visitors as they all follow the mantra, “guest equals god”.

Nepali people are difficult to characterize as they are made up of 126 ethnicities, 123 languages and 10 religions. Although, they are said to live in harmony, greeting each other by joining their hands, bowing and saying, “namaste”.

Hinduism is the country’s lead religion followed distantly by Buddhism among others. The mix of religions cascades into the country’s customs, traditions and social structure. For example, it is illegal to slaughter a cow – the country’s national animal – because it represents motherhood and wealth in Hinduism.

The caste system

Nepal’s society is influenced by a Hindu caste system where each person’s identity falls under one of four main categories once they are born.

The categories are hierarchical and supposedly dictate each person’s role in society, how others treat them, and their expected career path.

From top to bottom on the hierarchy, these categories are Braham, Kshatriya, Vaisya and Sudra, representing occupations such as a priest, soldier, merchant and labourer respectively. Outside of these four groups is a caste called the Dalits – the lowest class in the land known as the “untouchables”.

There are 4.5 million Dalits in Nepal, according to anti-caste discrimination organisation International Dalit Solidarity Network.

Female Dalits can barely breathe under the weight of caste and gender discrimination. They have no control over resources such as land, houses or money. They cannot apply for an occupation out of their caste’s reach without potentially facing violence, evictions or destruction of property. They are also “extremely vulnerable” to being trafficked or sexually exploited as some are looked down on as a “sex worker,” the organisation says.

Sexual exploitation is not exclusive to Dalit women, however.

In Nepal, most of the population are at high risk of exploitation and trafficking because the country is home to one of the biggest root causes of modern slavery, Walk Free Foundation says.

The answer is poverty.

Nearly a quarter of the country’s population, about seven million people, lived below the international poverty line of $1.25 a day in 2011, according to economic development agency Asian Development Bank. While this is high, it is a vast improvement compared to 68% of the population living in poverty in the country in 1996.

Ticket to poverty

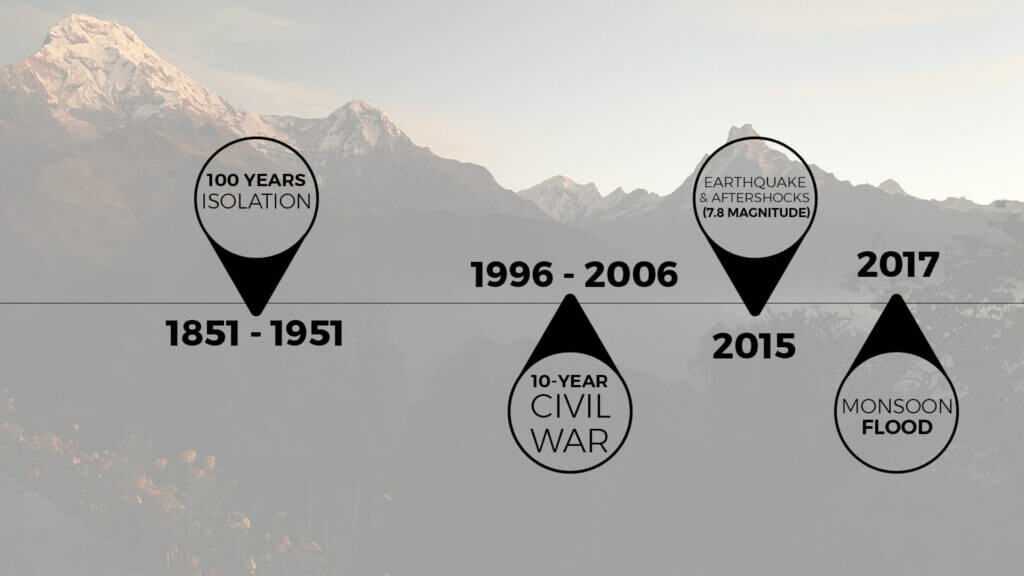

A civil war, earthquakes and a flood have helped sink the country in economic struggle and, in turn, poverty.

To rewind the clock, Nepal lacked infrastructure, like roads and houses, while it closed its borders to the outside world for one hundred years until 1951. After this, its economy began to revive itself, but progress was short-lived when the country headed for civil war in 1996.

From 1996 to 2006, civil war broke out between the country’s government and a political party, which believed in Maoism, called the Communist Party of Nepal. The war ended in a peace deal in late 2006, but it left a trail of socio-economic destruction in its path.

The war killed 13,000 people and 150,000 people lost their homes.

Economic development – such as improving health, drinking water and roads – tourism and trade in the country also took a hit. But children in the country took the brunt of it, according to a US-based academic paper in 2009 called Nepal’s civil war and its economic costs.

During the war, the report says, “tens of thousands of children” were allegedly abducted by the political party’s soldiers while other children were exiled by frightened parents. It would have been difficult for those children to dodge poverty later in life .

Before the economy could catch its breath and recover, Nepal was shaken by a lethal 7.8 magnitude earthquake in April 2015. This was followed by a similar shake two weeks after.

When the dust settled, the United Nations says, more than 800,000 buildings were flattened and more than 8800 lives were lost. The total cost of damages was estimated to cost about $7 billion. The quake would have also pushed an extra 982,000 people below the poverty line, according to the Asian Development Bank.

While the economy was still knocked down, a monsoon flood swept across the country in 2017. Heavy downpours are normal in Nepal, but this unprecedented flood killed 160 people, destroyed 43,000 houses and damaged another 192,000 houses.

Barely human

The prevalence of modern slavery is also partly caused by an “extremely low” status of women in Nepal, according to a report in 2014 by Walk Free Foundation.

Because of this, women are likely to experience sex trafficking and exploitation.

Showing a glimpse of this, in 2020 Child Rescue rescued 274 Nepali females compared to just nine Nepali males.

In 2011, 26,000 girls and women worked in the commercial sex industry in Nepal. Half of them were under 18 and working in Kathmandu Valley, which is a vast valley surrounded by four giant mountains and is home to three of the country’s biggest cities, including the capital.

On top of trafficking, women can experience forced marriage, opening the door to marital rape and forced reproduction. During menstruation, women can be seen as “unclean” and compelled to live in a shed with barely any food.

Women hardly speak out against these immoral acts because they fear being stigmatized.

Single young women, who do not have the provision of a man, are especially vulnerable to trafficking because they are desperate for work. Our border agents have stopped many girls and women, who were falling for fake jobs, from crossing the border.

Another part of this discrimination manifests itself in the form of child marriages, despite the minimum age of marriage being 20 in the country. According to global human rights organisation Human Rights Watch, 37% of Nepali girls marry before age 18 and 10% marry before age 15.

Nepal, however, has taken steps to tackle gender discrimination after it wrote a new constitution in late 2015.

For example, a third of parliamentary seats are now reserved for women, according to an academic report last year titled Conflict, Disaster and Changing Gender Roles in Nepal: Women’s Everyday Experiences. Although, these seats are often taken by “elite” women who have high education and vocational qualifications, leaving out a bulk of women in rural areas.

Desperate for a penny

Nepal has many large business sectors, including tourism, textiles and brick production. But its chief sector is agriculture, which employs about 66% of the population, farming mostly wheat, rice and maize. The sector helps reduce poverty too or, at least, stops people from slipping further into it.

Nonetheless, the country still lacks jobs.

According to a report in 2014 by Walk Free Foundation, Nepal’s economy needed to create 500,000 new jobs each year, but it was only making about 380,000 jobs.

Therefore, Nepali citizens are desperate to find work outside of the country. However, they risk being hooked by fake job opportunities that lead to sexual or labour exploitation.

In 2011, one in four Nepali households had at least one person living in another country, according to a report in 2016 by human rights agency International Labour Organisation.

For women in the country, some are paid peanuts even if they did score a job.

Half of the working women in Nepal in 2016 were not paid a penny for their work, while more than 70% of working men were paid in cash, according to the Ministry of Health Nepal.

Nepal, in fairness, is trying to protect its citizens from sexual exploitation and trafficking. It allocates a slice of its budget to fight the cause, trains law enforcement and has fined some fraudulent recruitment agencies among other measures.

Baking bricks

Sex trafficking and exploitation are not the only forms of modern slavery plaguing the country – bonded labour also runs rampant. According to Walk Free Foundation, about 547,000 Nepali people were in bonded labour in the country in 2011.

Impoverished families can get trapped in bonded labour, also known as debt bondage, for years. Given seven million people in the country earn about 45 cents US a day, many poor people take loans from employers or landlords if they are hit with an emergency, such as an illness, family death or simply not having enough money to make dinner.

To pay back their moneylender, the impoverished person will often work for them. But this labour is often under minimum wage.

One of the worst strands of bonded labour is child labour.

In 2008, about three million children in the country were in the “workforce” with 1.6 million in child labour, working in hotels, agriculture, tea shops and night entertainment. Although, many work in brick factories where they bake or burn bricks made of clay and shale.

Some of these children have entered work after dropping out of school.

According to anti-poverty in Nepal organisation Kidasha, primary school enrolment rates are high at 97%, but 45% of those children eventually drop out. One in four children live in impoverished families, the organisation says, and often the parents will send a child to work rather than receive an education.

Child Rescue sees this first hand, with 79% of those we rescue having an incomplete education.

Treacherous roads

While the country battles sex trafficking and exploitation, child labour and – the overarching problem – poverty, it also lacks the appropriate healthcare to care for all of its citizens.

To reel back the years, Nepal’s health system was severely damaged during the country’s decade-long civil war. More than 1000 health posts in rural areas were destroyed and more than a dozen health workers were killed, according to a report in 2010 by UK-based scientific publication BioMed Central.

After, 1,100 more health posts were brought to their knees by the earthquakes that rattled the country in 2015, according to US-based anti-poverty organisation The Borgen Project.

Today, only 60% of households in the country have access to health facilities within a 30-minute drive.

Rural areas suffer the most, partly because it is challenging to build roads in the country’s rugged terrain. And if there are roads, most of them are poorly paved or not paved at all. For instance, the distance between Kathmandu and another city in Nepal called Hetauda is 54 miles, but it takes about six or seven hours to travel.

This is not a trivial issue.

The rate of maternal mortality was about 462 women per 100,000 births in low-income countries, such as Nepal, versus just 11 women per 100,000 births in high-income countries in 2017, according to the World Health Organisation. The difference is pinned on the ability to access healthcare.

Child Rescue’s operations also face challenges from these roads. At the quickest, it takes them one week to travel to all fourteen of our border stations in the country, driving about 600km.

It is also common for a survivor, who is rescued at a border, to stay in one of our shelters between one to five days while she waits for her family to pick her up. In some cases we cover the cost of travel otherwise they cannot afford the journey.

Pandemic

While Nepal has had its share of nationwide stresses, such as civil war and natural disasters, the Covid-19 pandemic did not spare any country early this year.

So far, the pandemic has killed more than 2000 people in the country, and a bulk of the population could be heading for extreme poverty, which is defined as living on less than $1.90 a day.

According to the World Bank, the pandemic is likely to push between 88 and 115 million people worldwide into extreme poverty this year, with the total rising to 150 million next year. The pandemic will “leave lasting scars” on Southeast Asia.

Nepal’s short history was devastating and, unfortunately, the skies are not yet clear. While it is an overwhelming idea to try and fix the country’s flurry of challenges, Child Rescue is trying its best to tackle one of its problems – child sex trafficking.

Last line of defense

In 2020, our border agents, who are all Nepali women, rescued 260 people. They monitor the borders, conduct interviews and spot trafficking victims before they leave the country. Last year, they rescued 321, mostly young women.

Once rescued, survivors are reunited with their families and taught about the risks and realities of human trafficking. Each rescue is not only a life saved, but a whole family better protected against trafficking for generations to come.

US & International

US & International Australia

Australia United Kingdom

United Kingdom